Funding cuts from the Trump era risk undermining initiatives to support and empower farmers in Haiti.

In the heart of Haiti, a transformative initiative is underway that not only nourishes the bodies of thousands of children but also empowers local farmers, fostering a crucial sense of community resilience. The World Food Programme’s shift towards sourcing school lunches from local agriculture exemplifies a holistic approach to addressing hunger while bolstering the livelihoods of farmers like Antoine Nelson. As challenges mount, the program’s sustainability becomes increasingly vital for the future of Haiti’s youth and its agricultural landscape.

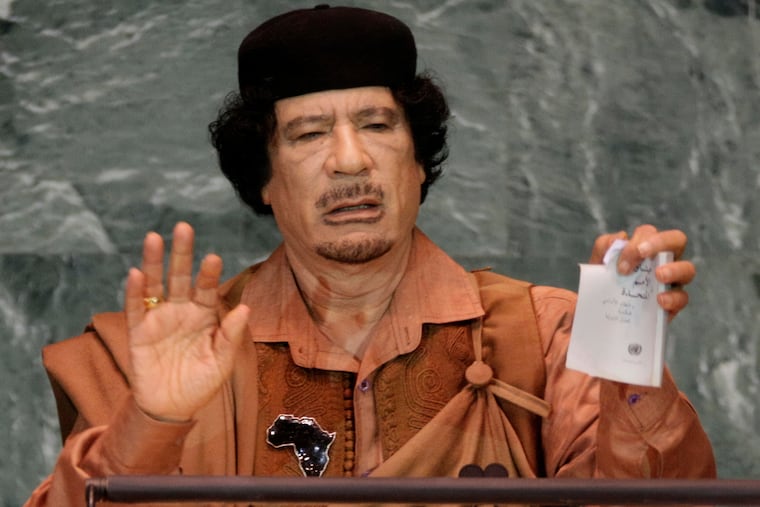

Oanaminthe, Haiti – It’s a Monday afternoon at the Foi et Joie school in rural northeast Haiti, and the grounds are alive with the vibrant energy of children in khaki and blue uniforms, playing together after lunch. In front of the headmaster’s office, a tall man in a baseball cap stands patiently in the shade of a mango tree. Antoine Nelson, 43, the father of five students at the school and a small-scale farmer, is there to help deliver the fresh food that sustains the children.

Nelson raises beans, plantains, okra, papaya, and other staples, directly contributing to what is served for lunch at the school. This connection between local farmers and educational institutions is a crucial development; he notes, “I sell what the school serves. It’s an advantage for me as a parent.” Nelson is part of a larger network of over 32,000 farmers across Haiti, whose agricultural products are supplied to the World Food Programme (WFP), a United Nations agency dedicated to fighting hunger and improving food security.

Together, these farmers help feed an estimated 600,000 students daily, a testament to the WFP’s evolving operational strategy in Haiti, the most impoverished country in the Western Hemisphere. The organization has dramatically shifted its approach, moving from importing food to sourcing a significant amount locally—72 percent of school meals are now procured within Haiti, with plans to achieve 100 percent by 2030. Additionally, the local procurement of emergency food aid has increased substantially in recent years.

However, recent challenges have emerged. The financial support from the United States has declined, creating a potential shortfall of million for WFP operations in Haiti over the next six months. As gang violence escalates, disrupting public services and displacing over a million individuals, the need for assistance grows dire—5.7 million Haitians face acute hunger as of October, a number that exceeds the WFP’s current capacity to respond.

Wanja Kaaria, the WFP’s director in Haiti, has emphasized the ongoing struggle: “Needs continue to outpace resources. We simply don’t have the resources to meet all the growing needs.” Nonetheless, for farmers like Nelson, initiatives such as the school lunch program have provided a crucial lifeline. He vividly recalls times when he struggled to feed his children breakfast or provide lunch money for school. “They wouldn’t retain what the teacher was saying because they were hungry,” he says. “Now, when the school gives food, they remember what the teacher teaches. It aids the children’s academic advancement.”

As funding challenges threaten the sustainability of food assistance programs, concerns arise regarding the potential reversal of progress towards empowering Haitian farmers and addressing food insecurity.

#WorldNews #CultureNews