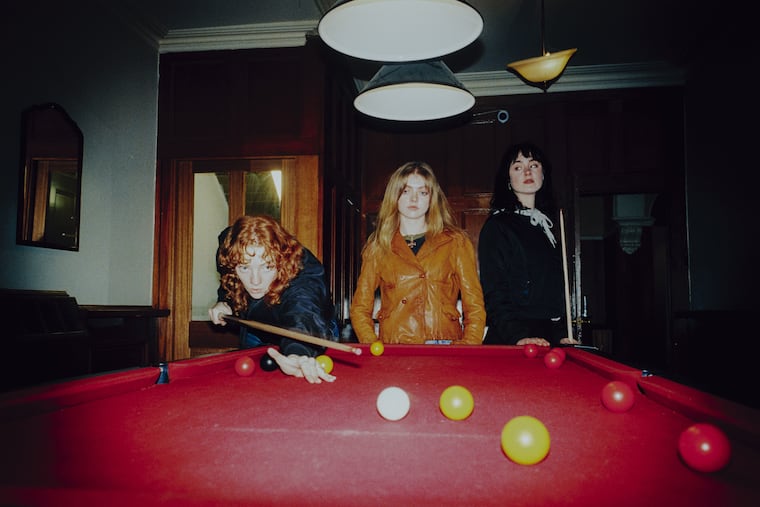

Private trash collection helped reduce pileups in certain neighborhoods amid the ongoing strike.

In Philadelphia, the contrast regarding municipal services can be starkly observed between various neighborhoods, particularly in the wake of the recent municipal workers’ strike that concluded early Wednesday morning. As residents in the more affluent Rittenhouse Square engaged in leisurely activities such as browsing the farmer’s market and enjoying the park, other areas, particularly in Kensington, exhibited troubling sanitation issues. There, overflowing dumpsters and scattered trash bags along the street presented a troubling image of neglect.

This disparity highlights the broader socioeconomic divide within the city, where pockets of extreme wealth coexist with areas plagued by high levels of poverty. During the strike, certain neighborhoods benefitted from the presence of business improvement districts (BIDs), which often have better resources to maintain cleanliness than less affluent areas that lack such infrastructure. In Nicetown-Tioga, for example, the community development organization Called to Serve actively engaged in trash collection efforts to combat rodent issues, demonstrating initiative in a time of need.

However, the challenges of waste management during labor disruptions cannot be understated. Neighborhoods with a mix of single-family homes and multifamily buildings, particularly in Center City, faced increased refuse without the robust private hauling options available to larger commercial entities. The city’s sanitation services are legally mandated to provide curbside pickup only to residential structures with six or fewer units, meaning that densely populated areas are often less reliant on public services.

Community leaders noted the impact of the strike on local sanitation efforts. BIDs, such as the Center City District, maintained their street-cleaning activities but faced increased strain. Local business leaders in South Philadelphia and Old City echoed that their primary role is to supplement city services, not replace them. This distinction is vital in understanding the ongoing challenges during such labor events and the essential role that community organizations play in mitigating service disruption.

While the city plans to resume regular trash collection next week, the immediate challenges remain. Civic leaders expressed concerns over public health implications due to overflowing trash at temporary dump sites. Community leader Casey O’Donnell highlighted the “huge volume of trash” accumulating in Kensington, while City Councilmember Anthony Phillips emphasized reliance on public services in neighborhoods lacking formal BIDs.

As Philadelphia grapples with these sanitation challenges, it serves as a reminder of the vital interplay between economic structures and municipal services, illuminating the stark differences in community resources and infrastructure. The management of trash and sanitation during disruptions illustrates how socioeconomic status significantly influences residents’ daily experiences. The city continues to balance its services amid these disparities, navigating a path toward restoring order as community leaders advocate for sustainable solutions.